The Sad Reason The Quagga Went Extinct

The plains zebra (Equus quagga) is one of the world's most recognizable animals, but there's one member of this species that no one has laid eyes on in over a century. The quagga (E. q. quagga), was a subspecies of plains zebra that once roamed the temperate grasslands of South Africa. The local natives named the animal in imitation of its guttural call, and it would later be enshrined in the scientific name of all plains zebras.

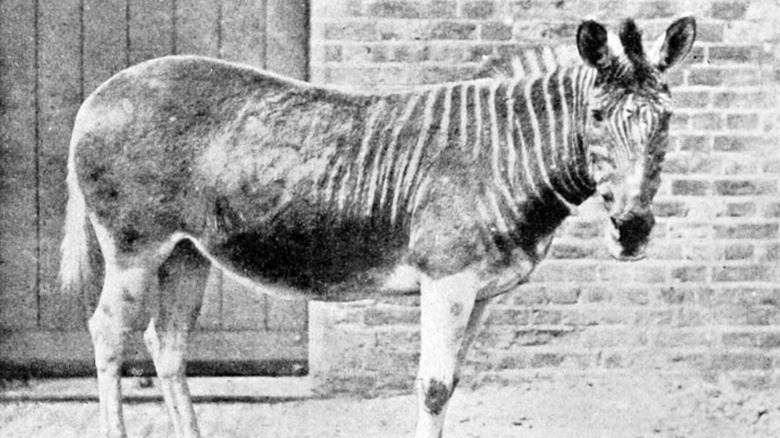

The quagga had one major difference from the plains zebras seen on safaris and in zoos around the world, and it has to do with the most famous of all zebra characteristics. Unlike other members of its species group, the quagga only had stripes on its head and neck. At the beast's forequarters, the stripes faded away to a coat of solid brown, creating what looked like a zebra and a horse blended into one.

The fate of the quagga, like the extinction of the dodo and countless other species, came about in the 1800s due to a combination of human hunting and agricultural expansion. Colonists prized the quagga for its meat and its beautiful coat, which was used to make leather goods. Quagga were also seen as an obstacle to farmers, who wanted to use the grasslands as feeding grounds for goats and other livestock. The last quagga on Earth died in a zoo in 1883, putting an end to a one-of-a-kind animal ... except, it might not have.

What life was like for the quagga

When quagga still roamed the South African grasslands, they lived similar lifestyles to the plains zebras that survive today. They were vegetarian grazers who roamed in herds of around 30–50 individuals. The herds were like families, with each quagga living out their whole life amongst the same group. They were polygynous animals, with male stallions maintaining a harem of female fillies. Sometimes, stallions would even fight to steal fillies from each other. Their natural predators were big cats like lions, cheetahs, and leopards, which would use the grasslands as cover to sneak up on unsuspecting quagga. To stay safe, one member of the herd would stay awake all night on the lookout for predators.

Stripes weren't the only difference between quagga and other plains zebras. Quagga had longer legs to support a lifestyle of constant migration. Accounts from the quagga's lifetime note that they appeared highly social, and were generally considered less aggressive than other plains zebras. Unfortunately, this may have made them easier targets for hunters. Despite their differences, quagga were constantly confused with other plains zebras, partly because the word quagga was once used for zebras of all stripes. One of the reasons that quagga went extinct is that nobody recognized their uniqueness and need for conservation.

The effort to bring back the quagga

When the last quagga died in captivity, and none were left in the wild, it was naturally assumed that they were gone for good. Once a species goes extinct, there is no bringing it back. However, in the 1970s, DNA analysis of quagga bodies preserved in museums revealed something surprising. It had always been assumed that quagga were a distinct species of zebra, but the DNA revealed that they were actually a subspecies of plains zebra, which still thrive in Africa. If the quagga's extinct genes still survive in plains zebras, there is a chance that the long-gone creature could return.

In 1987, a group of South African scientists launched the Quagga Project, an effort to bring back the quagga through selective breeding of zebras. Captive plains zebras with characteristics similar to quaggas, such as minimal striping and brown rather than black fur, were selected for breeding, producing foals that looked progressively more and more like quaggas. The process will take generations, each one inching closer to its extinct relatives. The project has been received with both hope and suspicion, as many argue that the results are simply different colored zebras, not a distinct subspecies. Efforts are far from finished, and it will take future genetic analysis to determine whether the quagga has really returned from the grave.