Dumb Things Everyone Overlooks In Dune

Back in 2021, "Dune: Part One" released to no small amount of acclaim. Really, the accolades just kept coming — six wins at the Oscars (of 10 nominations), and a long laundry list of other awards. A few years later, a sequel arrived with a similar level of aplomb — a ton of awards and nominations, in other words. And all of that is aside from the general level of popularity that both movies have won from legions of fans. That's all well and good, and as a movie, it's hard to deny that Denis Villeneuve's works are masterclasses in storytelling and filmmaking. But as works of science fiction, how well do they match up against real science?

As it turns out, author Frank Herbert actually wrote these books with grounded circumstances in mind; one of his original influences was the real-life attempt by the U.S. government to stabilize sand dunes in coastal Oregon in the early and mid-20th century. Herbert saw those efforts and used them as the basis for the relationship between his characters and the desert planet Arrakis.

Still, that's not to say that everything in the world of "Dune" is exactly accurate when it comes to the real science. In fact, there are quite a few things that most of us movie-goers prefer to overlook or simply accept as a part of this world. And while those things make for good fiction, they're not quite aligned with science as we know it.

Personal shields probably wouldn't work

Early in "Dune: Part One," the audience is treated to a short hand-to-hand fight sequence between Paul Atreides and Gurney Halleck, in which both characters activate a blue shield that flickers around their bodies and is meant to protect the wearer from certain kinds of damage. The shields allow for some pretty cool shots from a filmmaking standpoint, but scientifically, they probably wouldn't work.

In universe, the shields are explained by something called the Holtzman Effect, something which Frank Herbert himself described in the glossary of "Dune" as "the negative repelling effect of a shield generator." Of course, this effect isn't a real thing — it's just a fancy and fun bit of sci-fi world building. Not only that, but researchers have tried to think of ways to create similar kinds of force fields, but they really only exist in theory. One similar idea involves the use of the electromagnetic force; hypothetically, by creating a positive charge on an approaching projectile, it could be deflected by electric or magnetic fields. Others have posited that superheated plasma could be used to instantly vaporize incoming objects — a type of shield, though one that would function pretty differently. But regardless, any technology like that won't be around for a very long time, and neither of these hypothetical shield designs would actually work like those seen in the world of "Dune."

The aircraft are both more and less realistic than you might think

One of the especially stunning visuals present in the universe of "Dune" are the huge aircraft soaring high above the ground, their metallic wings flapping in the air. They look almost fantastical and completely unlike anything you'd currently see shuttling people through the skies, almost more like giant dragonflies than planes. (In fact, Frank Herbert reportedly referred to these ships as being insect-like in form.)

But here's the thing: These have a basis in reality. Generally speaking, aircraft like this are called ornithopters, a term that applies to any craft that propels itself by flapping wings in the same way a bird does. The idea behind them has also been around for centuries, dating back at least to Leonardo da Vinci, if not further, and experiments were conducted throughout the 19th and early 20th centuries, trying to find a way to get them to work. Unfortunately, they just never did, and ornithopter flights were never able to last very long, despite some small advancements in the field. In the end, engineers figured out how today's airplane wings work, and conventional designs using propellers, jets, and fixed wings were simply more practical at larger scales.

But scientists are still interested in ornithopters and have found a use for them. It's just not the use that you see in "Dune," namely as military and transport vehicles. Instead, they realized ornithopters would only really work at a small scale, and by using particular design specifications. In other words, they could be used for things like drones, in which case they could be both energy efficient and well-suited to busy places where hovering is useful. So, no, the huge ornithopters of "Dune" probably aren't realistic, but smaller ones might be.

Stillsuits might not work especially well

One of the most important and notable details when it comes to Arrakis is just how hot the planet is. Covered in deserts, it's a hostile place that has necessitated the creation of specific technology just for people to survive: the stillsuit. In the movie, the suit is described as doing a couple of things — namely, cooling the body and recycling sweat, turning it into drinkable water, all powered by nothing more than the body's movement. Overall, an elegant solution to all the hazards posed by Arrakis.

But on a scientific front, it's not quite that elegant. The "Dune" novels give little more (and occasionally contradictory) information on the detailed workings of stillsuits, and engineers have struggled to come up with an explanation. In short, the biggest problem is sweat. The process of sweating is more than just a gross human adaptation; it's actually the body's natural cooling method, and body heat being used to turn that sweat into vapor is what leads to cooling. But in the stillsuits, if that sweat is being taken directly from the skin, the body doesn't actually cool down; it just dries off, and heatstroke is still very much a possibility.

Even if it's assumed that sweat is allowed to turn into vapor, allowing the body to cool, there are still plenty of problems. That vapor would need to be condensed, or else the air inside the suit would become too humid for any more sweat to vaporize. (Or, if nothing else, the sweat is supposedly condensed back into drinking water.) But condensation would require extra energy (and a heat sink within the stillsuit) in order to work — a process that's never really explained.

Levitation isn't an easy thing to achieve

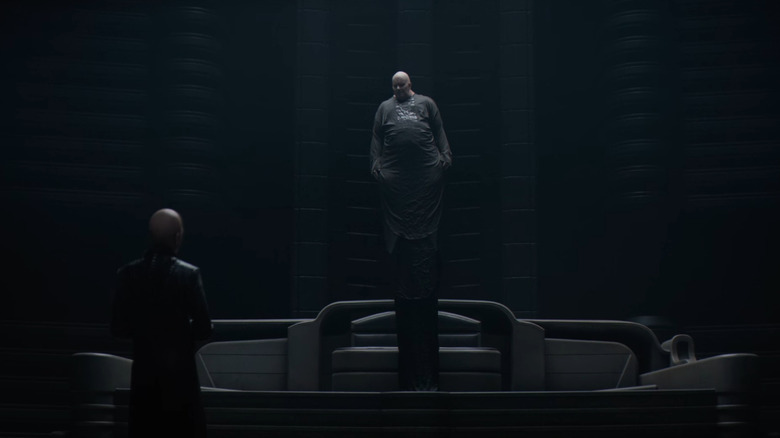

When the audience is introduced to Baron Vladimir Harkonnen, it doesn't take long for them to be met with a pretty imposing sight — the character slowly floating off of his seat, hanging in mid-air in the center of the shot. Most of the time the Baron is on screen, in fact, he's usually depicted levitating or seated in a floating chair. In universe, Frank Herbert also offers an explanation as to what's happening: The Baron is so overweight that he requires something called a suspensor suit. The glossary in the "Dune" novel explains that suspensors in general also run off of the Holtzman field — which is related to the Holtzman effect underpinning a number of other fictional technologies in Herbert's universe — and nullifies gravity within a certain area and limited by various other factors.

Of course, everything pertaining to the Holtzman effect, while internally consistent, isn't exactly real, so the only thing that can be done is looking for the closest equivalent. At the moment, levitation is largely achieved through the manipulation of magnetic fields. Quantum magnetic levitation in particular functions due to the Meissner effect, in which materials can be cooled to the point they act like superconductors, repelling any magnets placed above them. The problem is, of course, that this kind of set up needs to be really cold — liquid nitrogen levels of cold, in fact. Even systems that already use superconductors or diamagnetic materials have their problems, in that they require external power sources to continue functioning. And even if those systems were easier to turn into gadgets, current experiments probably don't allow the user to float anywhere, at any time, and under almost any circumstance. That's just the magic of science fiction.

Eyes don't change color that easily

When it comes to famous visuals associated with "Dune," bright, vividly blue eyes might be among the most well known. Within the fictional universe, that color is associated with the Spice, the coveted substance only produced on Arrakis which drives much of the conflict within the plot. Prolonged exposure to the Spice causes that change in eye color — something that can be seen in Paul's appearance early in the second movie. Is such a dramatic change in eye color possible, though?

Of course, the Spice found on Arrakis borders on magical, but if you were to try and find the closest real-world analogue to this phenomenon, you wouldn't really find any that perfectly match up. Very generally speaking, it is possible for eye colors to change. The use of certain medications — namely glaucoma eye drops or eyelash growth serums — have been noted to cause changes to the color of users' irises. That said, this effect is mostly seen in the case of lighter eyes, which then can turn darker, sometimes to a shade of brown. Not exactly the bright blue seen in "Dune." If you were to look in a slightly different direction, there's a medical condition called arcus senilis, in which a light blue ring can form around the edge of the cornea. The discoloration comes from a buildup of cholesterol and is generally a natural result of aging. So it's a somewhat similar color, but coming from a very different physiological source (at least, insofar as can be assumed, given the mystical nature of the Spice).

The Spice wouldn't likely have that many uses

The Spice found on Arrakis is many different things within the plot of "Dune." Narratively, it effectively serves as the main driver for political tension across many different factions, with control of Spice production being something worth killing for. Chemically, though, it's quite a few things besides that.

In "The Science of Dune," Carol Hart explains that the Spice — also called Melange — serves many different purposes to many different people. The Guild Navigators require it to safely pilot the spaceships that cross between planets. The Bene Gesserit use it in their rituals to commune with previous Reverend Mothers. The Fremen consume it as a normal part of their daily diet. And noble families on other planets across the Empire take it recreationally and experience some level of increased life expectancy, according to the original novels.

That's a lot for a single substance to do, and not all of those effects have real-world analogues. Namely, Hart points out the fact that, at least as of now, there's no miracle drug that can guarantee increased life expectancy. And, well, seeing across the entirety of space isn't exactly something that any substance on Earth can accomplish, either. As for the other effects, though, Hart does mention that they resemble those of hallucinogenic substances such as LSD. Even the varied effects are fairly accurate, as hallucinogenic compounds don't always affect everyone in the same way.

The giant sandworms aren't exactly worms

Across both of the "Dune" films, the audience is treated, on multiple occasions, to the terrifying sandworms that crawl beneath the feet of our heroes. The sight of shifting sands always brings with it a sense of dread, that's then followed up by horror as the monstrous beasts lurch up from beneath the ground. At least, until the second film, in which the worms play a slightly different role: gigantic mounts barrelling through the sands, carrying the members of the cast on their backs.

Here's the thing, though: Biologically speaking, they're almost nothing like the worms you'd find on Earth. The problem is in the way that they move. In "Dune," the sandworms are typically shown rushing forward at blinding speeds and with little deformation to their bodies. But the worms that you'd find in your garden can't move like that; they have pockets full of liquid that they can manipulate in a wavelike fashion, essentially scooting forward along the ground. (Real worms are also considerably more squishy than the giant sandworms of Arrakis, which seem to possess some kind of solid outer shell.) And though snakes and worms share some similarites in their movements, the sandworms don't even move like snakes, which typically slither side to side in order to propel themselves forward.

The closest analogue that scientists can think of are a very specific group of animals known as amphisbaenians, or worm lizards. They utilize something called rectilinear locomotion, in which the skeleton slides around inside of the skin, allowing the creature to move without sliding or scooting. Amphisbaenians even burrow underground, much like the sandworms, but they can't do so at the incredible speeds seen in the movie. After all, moving through sand means a lot of friction, so high speeds aren't easy to achieve.

Travelling faster than light is complicated

At various points throughout both "Dune" movies, vague allusions are made to the way in which space travel works in this universe. More specifically, early in the first film, lip service is paid to the Navigators of the Spacing Guild, who use Spice to plot courses through space and guide ships on interstellar journeys. Little more is said, though, outside of a few appearances of their ships, called Heighliners. Denis Villeneuve apparently intended to include more information on the Spacing Guild in the second film, but there's still little information to go off of.

Turning to the novels, though, space travel is pretty wild. In "Dune," ships travel great distances by folding space — another thing made possible by the universe's fictional Holtzman effect. That allows ships to travel from one place to another almost instantaneously, albeit with some other complications. Practically, that also means that the ships are achieving faster-than-light travel.

For one, according to the known laws of physics, any object can't travel faster than the calculated speed of light, which acts effectively as a universal speed limit. Only massless objects can move that fast. So a ship travelling that fast definitely isn't possible. And even the idea of folding space is a little shaky. Technically speaking, wormholes are a theoretical object that would seem to align with the space folding seen in "Dune" — they act as a bridge between two different points in spacetime, and they're not ruled out by the general theory of relativity (just one of Albert Einstein's major breakthroughs). But there's a catch: Objects, such as spaceships, probably can't move through them all too readily, so using them for travel is still an impossibility, even in theory.

How dangerous is space travel in this universe?

When references are made to the use of Spice when it comes to space travel, it's painted as not only being useful, but vital. More specifically, the Navigators of the Spacing Guild are said to use it to plot safe paths through the stars, and without it, interstellar travel wouldn't even be possible. All in all, it's a pretty good explanation for why the Spice is so valuable. The novels give a bit more lore on that front, explaining that the dangers of folding space come in the form of a strange possibility: materializing inside of a solid object. Obviously, that's not a great result, but without someone to properly see through folded space, it could happen.

Ignoring the accuracy of space folding as a means of travel, what would you find if you just looked at the risks involved? How likely is it that a ship moving instantly through space would actually materialize inside of a planet? Statistically speaking, it's probably not that high. Space is pretty empty on the whole, and if you were to evenly spread out all matter, the universe would have a density of only about 6 hydrogen atoms per cubic meter. Of course, matter isn't spread out evenly, but even in more populated areas of the universe, things are still pretty far apart. Asteroid belts are more empty space than minefields of floating rocks, and even the huge asteroid that was reported to just barely miss Earth was still millions of miles away.