The 10 Strangest Deep Sea Creatures Ever Discovered

The world is full of strange creatures, and researchers discover new animal species every year. The oddities of fauna tend to become ever so much stranger when we leave the dry land and turn our gaze to the depths, too. Humanity has only explored around 5% of the planet's oceans, but even though we still know very little, what we do know is enough to vouch with absolute certainty that things get pretty weird down there.

You may have heard of the various prehistoric sea animals that are pure nightmare fuel, and the oceans are still full of dangers. However, some of the most peculiar deep sea creatures aren't necessarily dangerous to humans at all — though they may be extremely fearsome to their own desired prey. What they definitely are, though, is impressively strange. Some of them are able to survive in ways that are hard to wrap your head around. Others have bodies that simply beggar belief, while others still are so mysterious and elusive that one can't help but be impressed by what little we know about their existence. The following deep sea animals are very different from each other, but they have one thing in common: They rank among the weirdest creatures that humanity has discovered.

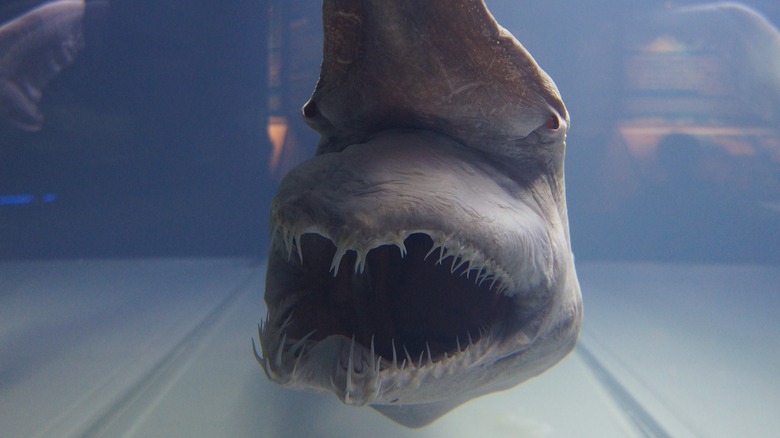

Goblin Shark

When marine life gets strange enough, it doesn't necessarily adhere to the same shape all the time. On the contrary, if we go deep enough, there's a decent chance of encountering truly alien-looking things ... and, perhaps even more unnervingly, comparatively unassuming animals that can suddenly whip out an absurd physical feature that you — or its prey — would never in a million years see coming.

The goblin shark (Mitsukurina owstoni) is a prime example of the latter thanks to its peculiar jaw build. For much of its time, this up to 20-foot deep ocean shark looks mundane enough as sharks go, except for its uncommonly long snout. However, when the sensitive electroreceptors of said snout inform the goblin shark that it's in the vicinity of food, the predator's face changes shape suddenly and very dramatically. At lightning speed, the goblin shark unleashes its ability to extend its jaws out of its head, which looks a bit like it's launching a bear trap from its face. This allows the shark to catch prey simply by slowly swimming around, and firing its jawbone forward to snag its next meal in its jagged needle teeth.

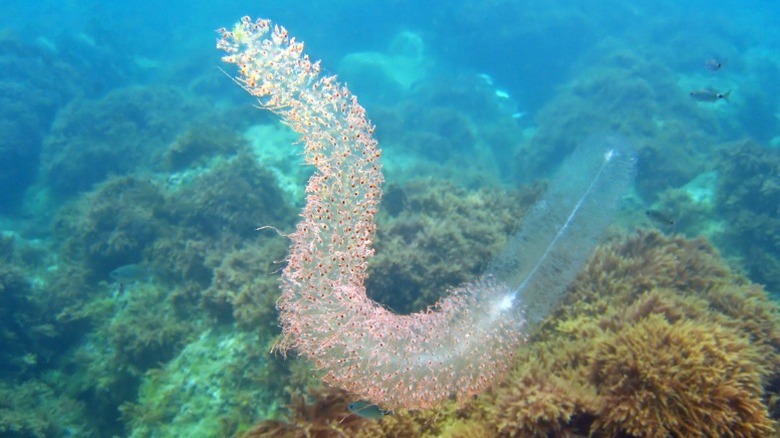

Giant tubeworms

Giant tubeworms (Riftia pachyptila) seem like something a video game player might come across during a particularly challenging level. Colony clusters of these gigantic worms that can grow up to 6.6 feet long might be strange to look at, but fortunately, these marvelous creatures are completely harmless to humans. This isn't just because they like to hang out in depths that range from 6,200 to 11,800 feet, and thus have a hard time reaching us. No, giant tubeworms are chill guys who pose no danger to any animal whatsoever. This is because they don't actually eat anything. Instead, the bacteria inside them allows them to survive on sulfur alone.

This peculiar method of survival requires R. pachyptila to form colonies around hydrotermal hot water vents, where the sulfur they need is abundant. They've become very good at this, too. If one hot water vent closes off and a population dies, the larvae will make its way to a new one, soon forming a new giant tubeworm squad of their own.

Scientists have no idea how the tubeworm larvae pull off this migration, but that's not the only mystery surrounding these resilient creatures. They were once thought to only live on the sea floor surrounding the hydrothermal vents, already a strange place to find life in the Pacific Ocean, but in 2024, a team of researchers found a colony of smallish, 20-inch giant tubeworms thriving in thermal cavities under the sea floor ... where only bacteria and viruses were thought to be able to survive.

Japanese spider crab

Godzilla and other gigantic kaiju monsters are a Japanese invention, and considering some of the species that live in the seas of the region, it's no surprise that the nation's popular culture has come up with its share of huge monsters rising from the seas. After all, you only need to scale up the Japanese spider crab (Macrocheira kaempferi) a bit, and even without some of the strange sounds heard in the ocean, it would fit right in a classic monster movie.

From a human standpoint, of course, the Japanese spider crab needs no scaling up. When this massive sea arthropod spreads out its front claws, their span from tip to tip can be up to 12.5 feet — well over twice the height of an average adult. It also has plenty of time to haul its impressive size around, given its estimated life span can reach 100 years.

Despite its foreboding size and appearance, the Japanese spider crab fortunately poses little threat to humans — despite old sailor legends that have suggested otherwise. While they're technically omnivores, they prefer to scavenge the sea floor in their native depths of 164 to 1,640 feet, and only occasionally grab a small fish or crustacean to feast on if they happen to find a target that doesn't require too much effort.

Barreleye fish

Even with the knowledge that the sea features absolutely all sorts of fish, you'd be forgiven for not knowing to expect the sheer oddness of the barreleye (Macropinna microstoma). Not only does this particular denizen of the Pacific Ocean have a completely transparent head, but its eyes are actually located inside its head, which means that it's quite literally watching the ocean from the inside. What's more, the eyes aren't where you'd expect them to be — instead of the small dots on the front of its head, the barreleye observes the world with those green globules located inside its head, roughly where you'd expect the brain to be. Because that's not enough design weirdness for one fish, the eyes also look directly upwards.

There's a reason for this strange evolutionary experiment, though. The barreleye uses its peculiar ocular setup to thrive in its preferred depth of 2,000 to 2,600 feet, which is a "twilight" zone where the sea starts to fade to complete black. Living as deep as it does and being only around six inches long, the barreleye poses little danger to human-sized creatures, but it can definitely be an unexpected menace to its preferred zooplankton prey. The barreleye's weird but keen eyes are attuned to seek prey directly above it. Once it locates and catches its target, it has a final little quirk in store: The barreleye has the ability to turn its eyes toward the front, so it can watch its meal as it consumes it.

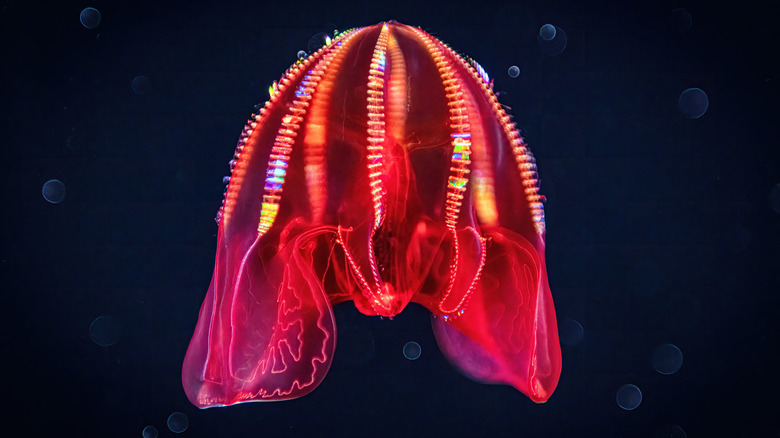

The bloody-belly comb jelly

Imagine swimming in the sea and suddenly seeing a large, red disco ball lined with rows of bright colors slowly making its way toward you. Granted, it's an unlikely scenario, given that the bloody-belly comb jelly (Lampocteis cruentiventer) lives at depths of 820 to 4,900 feet — but it illustrates the colorful ctenophore's sheer outlandishness.

In reality, of course, you probably wouldn't see the animal coming at all. The bloody-belly comb jelly has adapted to survive life in the ocean's twilight zone areas by developing the signature blood-red color of its stomach, which may seem like a fairly counterintuitive survival strategy to humans. However, the color actually serves as a decent camouflage in the depths, since red light comes across as borderline black in the bloody-belly comb jelly's particular living environment. Handily, the light also masks the translucent creature's innards, because otherwise the prey it's caught and eaten might be visible through its body.

The rows of vibrant colors that add to the bloody-belly comb jelly's otherworldly color scheme are actually tiny, iridescent hairs known as ctenes, which it uses to swim. The colorful appearance is created when the light in the ocean's twilight zone catches the ctene plates as they move.

Gulper Eel

The gulper eel (Eurypharynx pelecanoides) is also known as a pelican eel, and both monikers are a great fit for the creature's extremely strange physique. In its basic form — if the term applies in this particular animal's case — the 3.3-foot gulper eel is a thin creature with a peculiar, extra-wide mouth that gives it the appearance of a dull, wriggling arrow. However, at the drop of the proverbial hat, this predator can stretch and balloon its mouth, throat, and stomach to absurd proportions, taking in far bigger prey animals (mostly squid and crustaceans, though it also munches on seaweed) than its default shape would seem to allow. The water that it swallows with its intended target will exit through the gills.

Another denizen of the ocean's twilight zone, the gulper eel lives at the depth of 1,600 to 9,800 feet. Unfortunately for the animal, its strange physical properties also include a few things that posit problems for a deep-sea predator. It has a comparatively bad eyesight and is a fairly weak swimmer, so both mobility and locating prey can be an issue. Fortunately, the gulper eel has a way to get its prey to come to it instead, courtesy of a red, bioluminescent tail tip that acts as a lure ... and once suitable prey arrives to investigate, it's gulping time.

Siphonophores

Siphonophores are strange, even among aquatic lifeforms. For one, they're not individual animals at all. Rather, they're massive, gelatinous colonies of interconnected zooids – small clone organisms – that work together form a vastly larger creature. When we say large, we mean large, too – the largest siphonophore that researchers have found and measured was 154 feet long and had a 49-foot diameter, which is more than enough to put this strange class of organisms in the conversation for being the longest animal in the world.

There are 175 different siphonophores that we know of. The best-known one is likely the Portuguese Man o' War (Physalia physalis), which is comprised of a gas-filled balloon "sail" that floats on the surface and a series of venomous 100-foot tendrils that it uses to hunt small marine life. Other siphonophores steer away from the surface, and variations of the theme may even live on the ocean floor.

Like the Portuguese Man o' War, siphonophores tend to hunt with venomous tentacles, which they then use to pull the incapacitated prey into their various mouths. Fortunately for other ocean-dwellers, these dangerous predators don't actively hunt prey. Instead, they're drifters that either use bioluminesce lures or simply wait for some unfortunate animal to happen across their stinging nematocysts.

Snipe Eel

The slender snipe eel (Nemichtys scolopaceus), or simply snipe eel, lives in the depths of 1,000 to 2,000 feet, though certain snipe eel types have been found far deeper, in some of the most extreme environments in which life can be found. They grow up to 5 feet long but are so impossibly thin that they doesn't weigh more than 1 pound. This is because the predator has developed the peculiar survival strategy of being almost entirely tail. Effectively, the animal is little more than a 750-vertebrae backbone, attached to a tiny body and head.

Despite this economy of design — or rather because of it — the snipe eel has its share of biological peculiarities. Its amazing amount of vertebrae is a world record, and its head is no less strange. Armed with a pair of huge eyes and long, toothy jaws that resemble a thin bird's beak and are always open, the snipe eel doesn't really have to hunt for food. Instead, its eternally open mouth enables it to simply just swim around and feast on the crustaceans that happen to end up too close to its teeth. Unfortunately, it has little defense against larger and stronger fish, and thus may very well end up becoming a seafood meal itself.

Greenland shark

The Greenland shark (Somniosus microcephalus) is a slow and comparatively sedate shark that lives in the cold ocean waters of the northern hemisphere. They can and do rise close to the surface, and have been known to eat prey that ranges from fish and sea birds to distinctly non-marine lifeforms — such as horses that have ended up in the water for one reason or another. However, researchers believe that they usually prefer depths that range up to 8,684 feet.

What sets the Greenland shark truly apart from its oceanic brethren is its sheer longevity. In fact, this rare shark species will likely outlive all of us. While your average great white shark might expect to live until the advanced age of 70, a Greenland shark discovered in 2016 turned out to be roughly 400 years old. This is hardly the age ceiling for these unique animals, either. Current estimations indicate that there could be several Greenland shark out there that have lived over 500 years.

As you might expect, an animal that can reach such an age isn't in the habit of hurrying anywhere. While their up to 24-foot size is fearsome, the swimming speed of a Greenland shark is only about 1.8 miles per hour, and some researchers have suggested that the only way it can catch prey like Arctic seals is by ambushing them while they're sleeping in the water.

Colossal squid

We still know very, very little about the magnificent creature known as the colossal squid (Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni). In fact, it wasn't until April 2025 when a remotely controlled research sub belonging to the Schmidt Ocean Institute managed to capture video footage of a live colossal squid in all of its tentacle-wringing, bioluminescent glory — and even then, the specimen in question was a small baby that was under 12 inches long. This is far removed from the adult animal's full size, which is thought to be up to 46 feet.

What we do know is that the colossal squid is the largest known invertebrate of the depths, and thus the entire planet. This hulking, elusive beast can weigh over 1,100 pounds, and ambushes its prey with massive tentacles that are covered in powerful hooks that can rotate a full 360 degrees each.

To give an example of the colossal squid's might, the species seems to commonly find itself in conflict with none other than the sperm whale, the fearsome toothed whale that can be up to 57 feet long and weigh as much as 45 tons (90,000 pounds). While this obviously gives the whale a fairly massive weight advantage, the encounters between the species may not be quite as one-sided as you'd think. In fact, the majority of sperm whales from the southern hemisphere bear numerous scars from their battles with colossal squids.