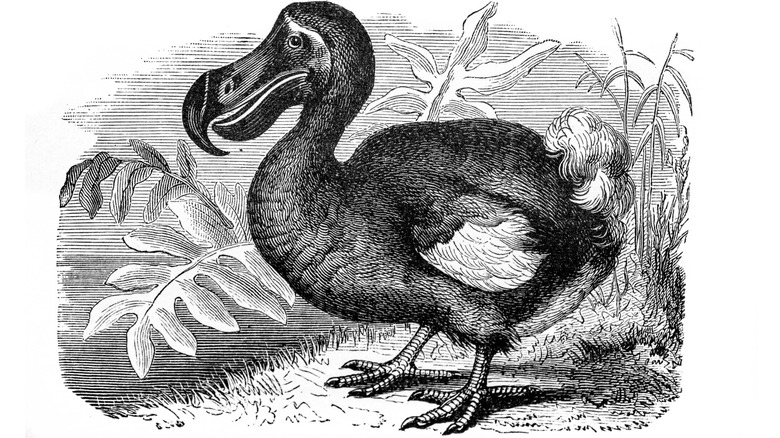

What If The Dodo Bird Never Went Extinct?

The dodo bird holds the unfortunate distinction of being arguably the best-known symbol of the Holocene extinction. Endowed with big bodies, miniscule wings, and short legs, these flightless icons were one-of-a-kind looking creatures, unique to a tiny corner of the world; the 775-square-mile island of Mauritius, in the Indian Ocean. On Mauritius, dodos were isolated from the reach of humankind all the way up until 1507, when they were spotted by a group of Portuguese sailors. A century and a half later, there wasn't a single dodo alive.

What caused the extinction of the dodo is a combination of several factors driven by human settlement on Mauritius, including hunting, deforestation, and the introduction of invasive species. The last confirmed sighting of a dodo was in 1662, and by the end of the century, the species was declared extinct. It left behind only two other members in its taxonomic family, Raphidae, those being the solitaires of the islands Réunion and Rodrigues. By the end of the 1700s, they too had gone extinct.

Dodos have gone on to become a symbol of the human destruction that has been labeled by many as Earth's sixth mass extinction event. After the dodo genome was sequenced in 2022 using museum specimens, some scientists proposed plans to revive the species by editing germ cells and inserting them into the embryos of chickens. To put the ramifications of this proposal into perspective, let's consider what the world would be like if dodos hadn't gone extinct in the first place.

Dodos might have been domesticated

When humans first made contact with dodos, they found the birds to be docile and trusting. They were easy to approach and catch, a fact that has since led to the widespread myth that dodos were dimwitted birds who walked obliviously into their own fate. In reality, the dodo's brain-to-body size was on par with its closest living relatives: pigeons. Pigeons are also commonly thought of as dim, but they have been shown to remember human faces, recognize words, count up to nine, and memorize hundreds of images, some of the highest indicators of intelligence ever observed in birds. The only reason dodos showed no fear towards humans is that, on their remote island home, they had never encountered the concept of a predator.

Many humans hunted dodos, but history might have played out differently had we chosen a different route, and aimed to domesticate them. After all, they showed a willingness to interact with our species. Furthermore, the aforementioned pigeons, which are the closest living relatives of the dodo, have successfully been domesticated by humans to multiple ends, most notably the carrier pigeon.

Dodos didn't have the working potential of carrier pigeons, and their meat was unpopular as well, but people have made pets of far less likely animals. There were some early attempts at domestication, but they attempted to do so by shipping dodos to Europe, a trip that the birds almost never survived. Perhaps a more concentrated effort in their actual homeland would have proven more fruitful.

Dodos might have saved the endangered plants of Mauritius

When a species goes extinct, it isn't just those animals that suffer. Extinction kicks off a butterfly effect that reverberates throughout entire ecosystems, toppling the balance of nature, and making conditions ripe for further extinctions in the region. This has certainly proven to be the case with the loss of the dodo, and the consequences it has had on the native plants of Mauritius. With its isolated position providing unique conditions for life, Mauritius is home to nearly 300 plant species that cannot be found anywhere else on Earth. Most of those plants are now critically endangered.

Historically, dodo birds played an important role in maintaining plant life on Mauritius. By eating fruits and pooping out their seeds, dodos helped to propagate new generations of plants around the island. However, the extinction of dodos and other large animals on the island means that many seeds are no longer being spread. A 2023 study published in the journal Nature Communications found that 28% of Mauritius' native fruits and 7% of its native seeds are too big to fit in the mouths of any species that survive on the island. Dodos were one of the rare species that could eat those big fruits and seeds, along with the also-extinct giant tortoises. If they were still around to perform the vital function of seed dispersal, perhaps the flora of Mauritius wouldn't be facing such a grim predicament.