Why Scientists Hate The Term Missing Link When Studying Evolution

If you've ever watched a documentary about the history of life on Earth, chances are you've heard the term "missing link." Applied to our own evolutionary story, it conjures a vivid image: a half-ape, half-human creature lumbering out of the mists of prehistory to connect us to our ancestral roots. But here's the thing, scientists don't use the term, and most of them really, really wish you wouldn't either. Exciting as it sounds, "missing link" is simply a relic of early 20th-century thinking that's misleading at best and fundamentally wrong at worst.

The idea of the missing link suggests that evolution is a kind of ladder, which is one of the things people get wrong about evolution. Linear and goal-oriented, this version of the evolutionary story implies the biological picture is incomplete until a certain species shows up at the "top," whatever that means. But species don't evolve in tidy, well-defined stages. In fact, thinking of evolution in terms of steps, in which one species exists on a continuum of progression, is just a paradigm that we humans have tried to cast over natural phenomena to help us make sense of them. Steps imply an end point and act as a means to an end, but evolution is both the means and the end, no matter what point in an animal's evolutionary history you look at.

Transitional features do exist along evolutionary timelines, but even then, scientists prefer terms like "common ancestor" or "transitional form." That's because these discoveries don't so much plug gaps in understanding as they expand our knowledge base of what existed in the past. Missing links do little more than reflect our desire to assert order and reason in a chaotic, random universe. And recognizing that is the first step to getting somewhere truly interesting.

The tree of life, not the chain of life

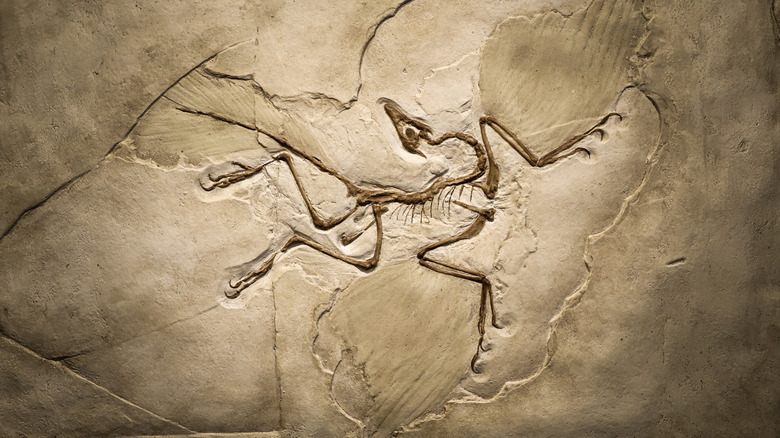

In 1863, paleontologist Hugh Falconer wrote a letter to his friend Charles Darwin about the discovery of Archaeopteryx, a bony-tailed, feather-clad animal that also exhibited several reptilian traits. Archaeopteryx was as much of a "missing link" between dinosaurs and birds as one could hope for, and today, media outlets and even educational and research institutions use the term to describe the creature. Darwin refrained from using the term, and it doesn't appear in "On the Origin of Species," published just a couple of years prior to Archaeopteryx's discovery.

That's because, though discoveries like Archaeopteryx help paint a picture of biological timelines, evolution looks more like a tree than a chain. Several branches of descendant species can exist alongside one another or even together with the ancestor species. In 2014, researchers discovered the 55-million-year-old remains of Cambaytherium thewissi, a hoofed, boar-like animal that some labeled a missing link between rhinos and horses. As it turns out, the animal was a cousin to the group of animals that includes horses, rhinos, and tapirs. But C. thewissi wasn't a link, it was simply a relative to horses and rhinos, wholly distinct from either's ancestral lineage.

The problem with calling any fossil a missing link is that it implies a single, definitive bridge between one species and the next. In reality, evolution is a complex web of changes, dead ends, and overlapping lineages. Transitional fossils like Archaeopteryx aren't final answers, but rather glimpses into patterns that continue to shift as new discoveries are made. These discoveries modify our understanding, not fill it out. When the media labels a species as a missing link, it often oversimplifies a process that's anything but, and in doing so, obscures just how dynamic and intricate evolutionary science is.

What to say instead of missing link

If the term "missing link" is outdated and inaccurate, why does it keep showing up in headlines and documentaries? Part of the reason is that humans naturally seek linear narratives with beginnings, middles, and ends. A story where apes become human with some transitional elements satisfies that desire. Failed branches and wildly intricate webs constitute a far less convenient reality. But it is the reality, and as such, scientists tend to prefer terms like "common ancestor," "transitional fossil," or "crown/stem group" when referring to evolutionary relationships.

These phrases reflect the nuanced reality that one species may exhibit traits found in multiple groups without being a direct ancestor, like the one missing feature in your wrist that's a clear sign of evolution or the "useless" part of your spine that's actually quite important. For example, the term "transitional form" captures the idea that a species can exhibit characteristics from both an older group and a new one without implying that it is the sole link between them (though, in everyday speech, "transitional" is still uncomfortably close to the concept of "link").

Crown groups include organisms linked by their last common ancestor, and stem groups are extinct animals that display some features of the crown group they're a part of. Studying both can help clue researchers in to the order in which these features appeared on the evolutionary timeline. While none of these terms are as catchy as "missing link," they more faithfully represent how evolution, a concept with more than its fair share of misrepresentation in popular culture, actually works.