These Body Parts Are The Most Sensitive To Pain

If you have ever wondered why stubbing your toe or hitting your funny bone can feel like the most excruciating pain on Earth, you aren't the only one. Researchers behind a 2014 study were also curious about the parts of the body that felt the most pain, and they set out to complete a research project that would provide answers.

The 2014 Annals of Neurology study was run by Flavia Mancini and Armando Bauleo, and it involved measuring how precisely participants could identify individual stimuli on the skin at increasingly smaller intervals. The closer the two stimuli were when they could still be detected, the more densely packed nociceptors (pain receptors on the skin) likely were, suggesting that those areas are more sensitive to pain than others.

This study was the first of its kind, since it had previously been difficult to conduct a pain stimulus study without incorporating touch. In contrast, this study used laser pulses to deliver the pain without touching the body, though touch sensitivity and tactile stimulation measurements were also taken to compare. The study also included a participant with a rare condition that prevented them from sensing touch, and perhaps surprisingly, their sensitivity to pain was in keeping with the rest of the group. The results of this landmark study allowed the authors to create a body map showing the most and least sensitive body parts to pain, revealing significant differences across the human body. Let's take a look at the body parts that are most sensitive to pain.

Fingertips

As anyone who has ever had a papercut knows, the fingertips are extremely sensitive to pain — how can such a small cut cause such an intense sensation? This has now been proven in the recent whole-body mapping study, which showed that fingertips were incredibly sensitive to painful stimuli.

In the study, the fingertips were shown to be the most sensitive part of the body, as they were able to detect two distinct sources of pain at the closest possible distance. The average across all participants showed a distance of less than 5 millimeters, whereas other parts of the body needed a distance of around 3 centimeters to sense the same thing.

Other details of human biology help explain why the fingers would be so sensitive. The skin on the palm of the hands is known as glabrous skin, which refers to skin which is smooth and hair-free, and there are many receptors in these areas, packed very densely into a small space. This makes perfect sense, since our hands are the first parts of our bodies to touch objects, and they send information back to the brain about the nature of them. So the next time you feel silly at overreacting to a cut on your fingertip, remember it is an evolutionary advantage that the fingertips are the most sensitive part of the body when it comes to both touch and pain.

Forehead

If you've ever been floored with pain after a bump on the forehead, we now know why, as it has been shown to be among the most sensitive parts of the body, with only the hands getting more sensitive results. Participants in the study were able to detect distinct stimuli about 1 centimeter apart, which is much closer than other areas such as the lower back or calf. This is likely due to the complex network of cranial nerves in the head.

Across the 16 volunteers in the research study, the spatial acuity for successive stimuli on the forehead was less than 1 centimeter on average, with one participant sensing them just above 5 millimeters apart. One of the authors of the study, Flavia Mancini, reported that the results for pain sensitivity in the forehead are quite surprising, as they don't follow the general rule of more nerve fibers meaning more pain. "Somehow we must have learned to localise pain on the fingertips and forehead despite not having dense numbers of fibres there," says Mancini (via New Scientist).

This important distinction shows that the sensation of pain is a multi-faceted process, with the brain potentially processing the signals from receptors differently depending on where they came from. It is proof that the pain we feel is not simply dependent on the density of nerves in the area, but also on the brain's interpretation of the signal.

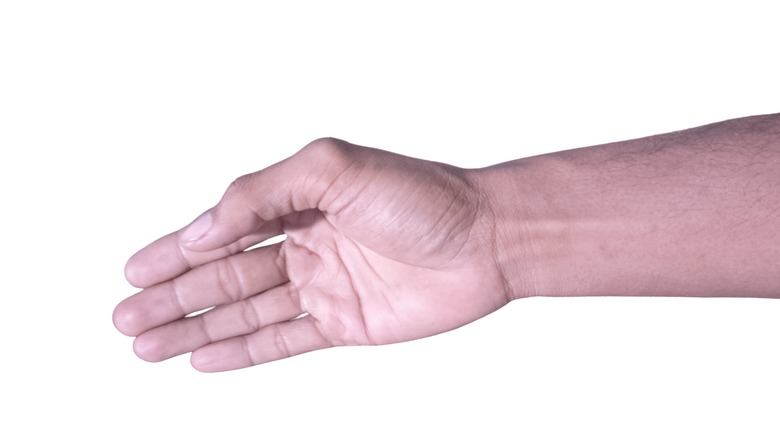

Palm

According to the 2014 study, the palm of the hand is one of the most sensitive areas of the body. Though its sensitivity to touch was already known, the study proved that the palm senses pain more than most other areas of the body, too. In fact, the threshold for detecting two successive stimuli on the palm was less than 1 centimeter apart on average, with only the fingertips sensing them closer.

This result is not a surprise, since the hands are packed with nerves and receptors, and they have many different types of nerve fiber. The glabrous skin on the palms is also the same as that on the fingertips, which is another reason that the results are so similar for both. This all makes sense from an evolutionary standpoint, since being able to sense details with our hands is a crucial skill that makes solving problems so much easier. Sensing instantly with a burnt palm that an object is hot will prevent more serious injuries. This super-sensitive nature of the skin on our hands is ultimately what allows us to make sense of the world so easily by touch, and — unfortunately — what also makes an injury there so agonizing.

Sole of foot

If you've ever stepped on a Lego, you will understand just how sensitive the sole of the foot is to pain. This pain perception study has confirmed that the seemingly disproportionate agony is not just your imagination, as the soles of the feet scored rather highly.

Though not as sensitive as some parts of the upper body, such as the forehead and underside of the hand, compared to the rest of the lower body, the soles of the feet are incredibly sensitive to pain. In the study, the average detection of two consecutive stimuli was just over 1 centimeter; compare that to the calf, which required almost 3 centimeters.

Since the sole of the foot is filled with mechanoreceptors (neurons that are made to transmit information about touch and pressure) with a small relative field, it is no surprise that it is able to sense different stimuli within a small distance. The sole also has glabrous skin that is similar to the palm, which enables the detection of sharp or hot objects while walking around. This acute sensitivity to pain allows us to prevent further damage occurring when a dangerous object is encountered.

Back of the hand

Following the extremely sensitive nature of the palm and fingertips, it would be reasonable to assume that all skin on the hand would have scored similarly in the spatial acuity study. However, this is not the case, with the hand dorsum actually scoring as the least sensitive of all the upper body parts that were tested.

The skin on the back of the hand is not the same as the glabrous skin on the palm. Known, for obvious reasons, as hairy skin, there is no need for this to be as sensitive to either touch or pain, since it is not common that we would touch anything with the back of our hand before the palm. It also isn't involved in fine motor skills such as writing by hand (something that can actually give you a cognitive edge) or tying shoelaces, so it makes sense that receptors don't need to be as small or densely packed.

In spite of its lack of sensitivity compared to the rest of the upper body, the hand dorsum proved more sensitive than many of the lower body parts that were tested. This result highlights the intelligence of the body's sensory system (just one part of the structural classification of the nervous system), saving the largest number of receptors for the critical areas, but still giving the other side of the hand a higher level of awareness than many other areas.

Top of the foot

In contrast to the dramatic pain felt on the sole of the foot, the top of the foot is much more resilient when it comes to sensing pain. According to the study, participants couldn't distinguish between the two simultaneous stimuli unless they were at least 3.5 centimeters apart, which is a marked difference from the 1 centimeter for the sole.

As with the hand dorsum, it makes sense that the top of the foot wouldn't need to be nearly as sensitive as the underside, since it is not generally coming into contact with the ground. Interestingly, the results for touch sensitivity rather than pain were very different, with the top of the foot being the second most sensitive to touch after the sole. This means a brush of something on the top of your foot can be easily detected, but fortunately, it is protected from the intense pain that the sole would feel if it encountered a sharp object.

Shoulder

Outside of the top three body parts that had incredibly sensitive pain detection — the fingertips, forehead, and palm of the hand — the shoulder scored highest of the remaining body parts included in the study. Simultaneous stimuli were detected at around 1.5 centimeters apart, which is not much greater than the results for the forehead.

This sensitivity to pain is crucial for preventing injury in the shoulder area. If you have ever had a frozen shoulder, you will understand how crippling it can be, affecting movement in the arm and impairing mobility significantly. Shoulder pain can take up to six months to heal, so prevention is definitely a better option than cure. The high sensitivity to painful stimuli means that damage to the shoulder caused by carrying overly heavy weights, such as from a workout or excessively heavy shopping bags, can be prevented by the quick signals sent to the brain. This could be the reason that the results for pain in the study were much more sensitive than touch, as preventing damage to such a critical joint system is more important than sensing gentle touch on the skin.

Lower back

In the 2014 spatial acuity study, the lower back scored right in the middle of the results, showing higher sensitivity than the majority of the lower body, but less than the highly sensitive areas higher up. Participants needed an average of 2 centimeters between successive stimuli to detect the individual pain points, compared to 0.5 centimeters for the fingertips and more than 2.5 centimeters for the top of the feet.

Though the back doesn't need to be overly sensitive to surface damage from sharp or hot items in the same way as the fingers or soles of the feet, nociceptive pain in the back due to strain and stress can cause significant mobility issues, so the ability to sense pain and send a signal to stop a particular movement is crucial. That's especially important when you consider that as much as 80% of the population of the U.S. will have lower back problems within their lifetimes, making it a serious source of economic stress. If the back was more sensitive to painful stimuli, then this number would be even more damaging, so the balance between alerting the brain to strain while not overreacting to every tiny stimulus is critical.

Forearm

As the upper body goes, the forearm was one of the least sensitive areas studied in this particular endeavor, with only the hand dorsum being less sensitive above the waist. That puts it at roughly the halfway point when the whole body is taken into account.

For successive stimuli, the forearm could detect the difference at an average of 1.5 centimeters apart, which is three times the distance needed at the fingertips. After all, since the forearm is not exploring objects and using implements in the way that the hands are, they have no need for the high number of nociceptors seen in the palms and fingertips.

This level of sensitivity also makes sense when you think about how we use the forearm for protection. If a projectile was thrown toward you, your forearm would likely raise to cover your face in defense, acting as a shield to the more sensitive body parts. The moderate sensitivity shown in the study means the arm can report back to the brain the level of pain present, to help assess the danger of the impact, without it experiencing serious pain throughout the day whenever you suffer a bump or a scuff.