The Huge Scientific Discovery That Could One Day Reverse Osteoporosis

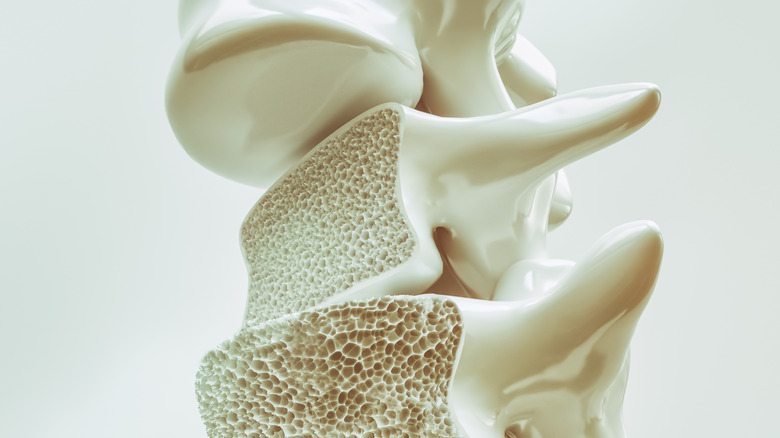

For many people, weakening bones in old age is an unavoidable fact of life. For some, especially post-menopausal women, such weakening is a chronic disease. Osteoporosis causes the skeletal system to lose its density faster than the body can repair and reinforce it. There are some treatments to help slow or stop the process, but there is no cure. At least, not yet.

A new collaborative study from Leipzig, Germany and Shandong University in Jinan, China has made a huge stride forward in the hunt for a cure for osteoporosis. Previously, researchers had linked a specific gene, called GPR133, with bone density and repair. What exact role the gene played, however, was still up in the air. So, the team devised a test on mice to observe the gene's activity. First, the researchers had to determine a way to activate the gene.

Using computer simulations, the team pinpointed a chemical called AP503 that could stimulate inactive GPR133 genes. This discovery alone was a huge breakthrough, but they still had to put the stimulating substance through its paces. Mice were sorted into groups: those with healthy bone density, those with symptoms of osteoporosis, and those that lacked the GPR133 gene altogether. Amazingly, both the healthy and the osteoporosis groups showed increased bone strength when the AP503 chemical was administered, while the GPR133-lacking groups showed no improvement in bone density. In other words, with the right gene-stimulating drugs, even those with inactive bone-repair genes may be able to reverse the disease.

How one gene determines the risk of broken bones

DNA is like a recipe book for making proteins, and genes are like the individual recipes. The GPR133 gene is responsible for activating specialized cells called osteoblasts, which rebuild and grow bone tissue. Osteoblasts work in conjunction with cells called osteoclasts, which break down damaged or old bone tissue to make space for new bone growth. People with osteoporosis often have excessive osteoclast activity and reduced osteoblast activity. To put it figuratively, their bone-cleanup crews are working overtime, while their bone-repair crews are on a permanent break.

The researchers from Leipzig and Jinan determined that the GPR133 gene holds the recipe for a protein that signals osteoblast cells to start working again. The connection was revealed through the use of "knockout" mice, which are bred to lack the GPR133 gene. In the knockout mice, the gene-stimulator chemical AP503 had no effect and they continued to suffer from brittle bones, while both healthy and brittle-boned mice with the gene responded to the drug with increased bone strengthening. This proved that the GPR133 has a direct connection to stimulating osteoblast activity.

The findings are especially encouraging for the 10 million Americans suffering from osteoporosis and the 44 million more that have low bone density. Whether the AP503 chemical will become the ingredient of an osteoporosis-reversal drug is yet to be determined. However, such insights into the specific roles of genes add to the huge strides being made in medical science to slow and even reverse aging. Drugs like metformin can reduce the risk of age-related diseases, while tai chi may slow aging in the brain. Now, drugs to slow aging bones may arrive sooner than believed.