What It Means When A Polar Vortex 'Breaks'

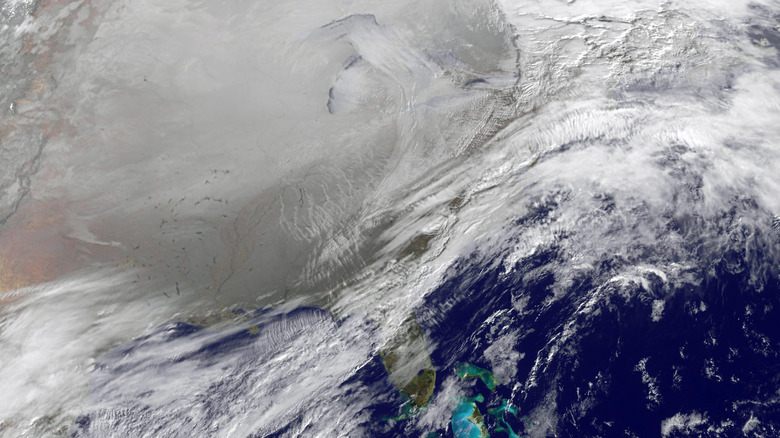

The term "polar vortex" seems to be popping up in weather forecasts more and more often, ever since North America got blindsided by a stunningly frigid winter back in 2014. The polar vortex isn't a new phenomenon, though. It's a normal feature of our planet. At both the north and south poles, there is a zone of low atmospheric pressure, where cold air swirls into a constant vortex. Typically, these rings of cold air stay centered around the poles, hovering between 10 and 30 miles above the surface. This is the status quo in Earth's high latitudes, where temperatures are almost always below freezing, but sometimes the effect expands beyond its normal boundaries. This is known as a polar vortex break, when cold air from the poles moves into the mid, or even low latitudes.

The polar vortices are surrounded by the polar jet streams, the two most powerful of Earth's jet streams, which are located between five and nine miles above the surface. The winds there can top 100 miles per hour, and they act like retaining walls that hold the cold vortices in place above their respective poles. However, jet streams can alter their course, moving further north or south depending on conditions. When these "retaining walls" expand, the polar vortex breaks. The results can be severe, as Arctic-level freezes blow through places that aren't accustomed to them. Over the past decade, however, the northern hemisphere has been getting much more familiar with this phenomenon.

The northern polar vortex breaks more often, with greater consequences

When a polar vortex makes the news, you can all but guarantee it's the northern one in question. The southern polar vortex is actually larger than its northern counterpart, but it is far more stable, rarely breaking beyond its normal boundaries. This has to do with the surface of the earth below the vortices. The northern hemisphere has more than two-thirds of the planet's land mass, while the vast majority of the southern hemisphere is taken up by oceans. The greater geographical variance in the northern hemisphere creates waves of air in the stratosphere that disrupt the polar vortex.

The southern hemisphere experiences far fewer stratospheric waves, which leads to less variances in the polar vortex there. One effect of this is that the southern polar vortex traps cold air far better than the northern polar vortex, creating the coldest temperatures on the planet. However, that cold air doesn't break away like it does in the northern hemisphere.

Human distribution follows that of land, with roughly 90% of the global population residing in the northern hemisphere. This means that breaks in the northern polar vortex have a bigger impact on infrastructure. In the U.S., breaks in the polar vortex often bring extreme weather to the major population centers of the midwest and northeast, including New York, Chicago, and Washington, D.C. These vital cities will likely see such events escalate going forward, as the polar vortex is breaking more and more.

The polar vortex keeps intruding on lower latitudes

The words "polar vortex" became a household term across America in the winter of 2014, when the Great Lakes region was slammed by six straight months of freezing temperatures. It was the coldest winter the region had recorded in 35 years, causing severe disruptions to travel and supply chains that drained $4 billion from the U.S. economy. At one point, the polar vortex drifted so far south that all 50 states experienced temperatures below freezing in at least one location.

Since that winter, the polar vortex has increasingly encroached on the continental U.S. In 2025, it is doing so again, for a very unusual reason. In November, a sudden stratospheric warming event occurred over Antarctica, causing a rare break in the southern polar vortex. This has had a domino effect across the globe, leading to rising air pressure around the north pole. As the pressure builds, the polar vortex is pushed further and further south, into Canada and the Midwest.

Sudden stratospheric warming events are periods of rising temperatures that happen roughly every two years around the north pole, but only every 60 years or so around the south pole. There's some debate over exactly what the impact of this phenomenon will be, and what role, if any, climate change may play in it (2025 is projected to be one of the top three hottest years ever recorded). It seems likely, however, that the country is in for a rough winter.