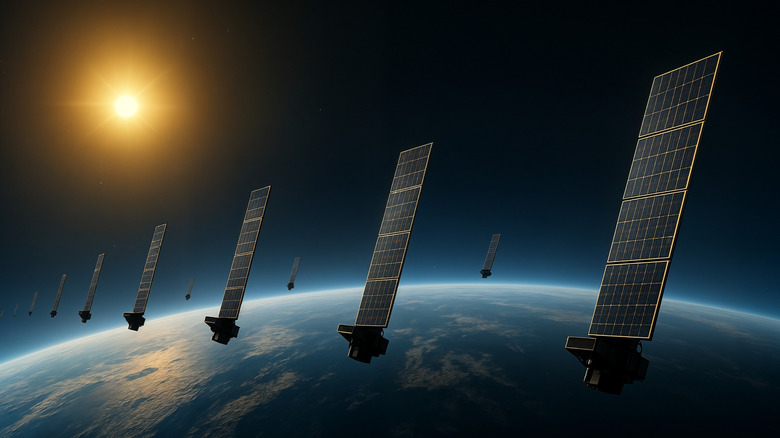

The Number Of Starlink Satellites That Have Fallen Out Of The Sky Might Surprise You

When the first group of Starlink satellites launched into low Earth orbit in 2019, hopes were high. The compact and relatively low-cost SpaceX satellites could improve internet accessibility, particularly in remote rural regions where technological infrastructure is otherwise lacking. The scale of the project is unprecedented. As of the writing of this article, there are 10,727 Starlink satellites in orbit, and SpaceX has ambitions to push that number to over 40,000 in the future. To this end, the company is launching dozens of satellites every week, but it's also losing them at an alarming rate. Between 2020 and 2024, more than 500 Starlink satellites fell from orbit. That's a concerningly high number already, but in 2025, the situation got much, much worse.

Astrophysicist Jonathan McDowell of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics has been tracking Starlink satellite reentries since 2020 on his website, Jonathan's Space Report. At first, the satellites seemed stable, with only two reentries in 2020, but the number soon climbed: 78 in 2021, 99 in 2022, 88 in 2023, and then in 2024, a massive leap to 316. That's almost one a day, and in 2025, it's even more. McDowell has recorded 1–2 satellite reentries per day this year, with as many as four falling in a single day. This has rung alarm bells across the astrophysics world, and it seems scientists have found the main reason for the recent leap in failures. Unfortunately, the problem happens to be the most massive thing in the entire solar system.

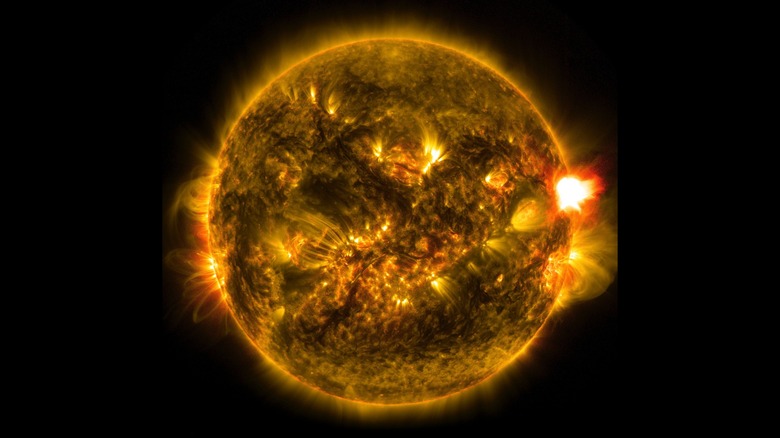

The sun is having an impact on Starlink satellites

In late 2024, the sun reached solar maximum, the peak of its 11-year solar cycle. During this phase, there is a dramatic increase in sunspots, solar flares, and violent eruptions of plasma known as coronal mass ejections. This time around, some scientists are warning that the sun could enter an even more dangerous phase that sees this increase in solar activity extended for another year or two. This is a big problem for SpaceX because higher levels of solar activity have a well-documented history of messing with human technology.

More solar activity means more solar winds, which travel through space at around a million miles per hour. In doing so, they carry charged particles from the sun's magnetic field, some of which enter Earth's atmosphere. When this happens with especially strong solar winds, like those experienced around the solar maximum phase, it can disrupt Earth's magnetic field and cause power outages. Now that we've extended our technologies to space, the consequences are growing.

Between 2020 and 2024, a research team headed by physicist Denny Oliveira of the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center tracked 523 fallen Starlink satellites, and noticed a clear pattern. In a paper published in Frontiers in Astronomy and Space Sciences, they demonstrate that satellites fall out of orbit more quickly as the solar cycle intensifies. That would explain the sudden spike in Starlink reentries that McDowell found starting in 2024. However, SpaceX's problems go beyond a temperamental sun.

Starlink may be sowing the seeds of its own demise

The sun's solar maximum is temporary, but Starlink's problems won't be. Even after solar activity quiets down, there's still another big problem to face. The number of satellites in orbit has seen a dramatic increase in recent years with the expansion of private companies into space, and it's getting crowded up there. As of December, 2025, there are an estimated 15,000 satellites in orbit around Earth. Around two-thirds of that collective are Starlink satellites, despite the project only having started in 2019. With the current rate of expansion, there could be more than 500,000 satellites in orbit by 2040, which would cause a serious case of Kessler Syndrome.

Kessler Syndrome is a scenario in which the space surrounding Earth becomes so overcrowded by satellites that they begin crashing into each other, sending massive amounts of space debris raining down upon the planet. The risk was first presented by NASA researchers Donald Kessler and Burton Cour-Palais back in 1978, but despite decades of warnings, we have been exponentially increasing the number of satellites in space.

Most Starlink satellites that fall from orbit don't cause harm on the ground because they disintegrate during reentry, but when that happens, metal compounds like copper, lithium, and aluminum get put into the atmosphere. We don't yet have adequate research to know how serious the effect of those compounds will be, but the increasing likelihood of Kessler Syndrome means we could find out all too soon.