The Strange Story Behind The Fascinating Discovery Of X-Rays

Scientific advances tend to be slow and meticulous affairs, built from incremental steps that eventually lead to a breakthrough. Such was the case with magnetic resonance imaging, which took decades to emerge from the discovery of nuclear magnetic resonance. On the other hand, there are major leaps in science and technology that happen in the blink of an eye and completely transform the world in the process. Wilhelm Röntgen's accidental discovery of X-rays falls squarely into this latter camp.

In 1895, Röntgen was attempting to replicate the work of fellow physicist Philipp Lenard who was at the forefront of cathode ray experimentation. Lenard was working with Crookes tubes, glass tubes which encased two electrodes in a near vacuum. When electricity was applied to the electrodes, the glass opposite the cathode would fluoresce from the impact of the cathode rays (eventually discovered to be electrons). Lenard created a small window in his tubes which he covered with foil, though which the cathode rays could pass, causing paper painted with pentadecylparatolylketone to fluoresce if it was within a few centimeters of the foil window.

Röntgen didn't have access to pentadecylparatolylketone, so he used barium platinocyanide instead. In order to better see the fluorescence of the paper, Röntgen covered his tube in cardboard to keep its light from outshining the light from his paper. When he fed power into the tube, he noticed his paper glowing even though it was multiple feet away, well outside the range of the cathode rays. The only explanation for the fluorescence was a new type of ray. Owing to its mysterious nature, Röntgen coined it an X-ray.

How the X-ray changed the world

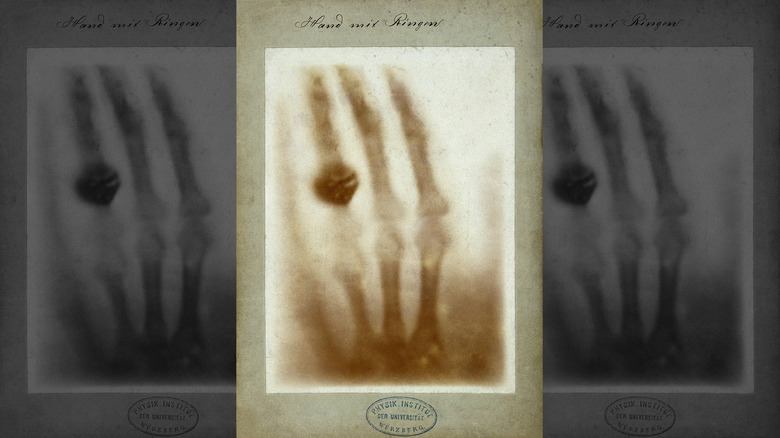

The path from the discovery of X-rays to their everyday use was remarkably short. The same day Röntgen first observed the X-ray, he discovered that he could see his bones projected onto the fluorescing sheet, and he found that X-rays interact with photographic plates. On the very day he discovered X-rays, he took the first X-ray photograph of his wife's hand. When he published his first paper on the phenomenon less than two months later, the news spread around the world.

It's hard to overstate how big of a deal X-rays were, and the scientific community of the time was aware of it. In the year following Röntgen's paper, over 1,000 scientific papers were written about X-rays. Within months of Röntgen's discovery, X-rays were being used by doctors, not just for diagnosing broken bones and finding foreign objects in the body, but as radiotherapy to treat cancer.

In just a few short years, X-rays directly led to J.J. Thomson's discovery of electrons and radioactivity which inspired Einstein's annus mirabilis in 1905. A few years after that, through the development of X-ray diffraction, it was shown that X-rays were electromagnetic in nature. X-ray diffraction was the tool that revealed the double helical nature of DNA in 1953.

In 1901, Röntgen was awarded the first Nobel Prize in physics. For his part, Röntgen remained humble, donating the prize money to his university and refusing titles of nobility. And perhaps most importantly, he opted to not patent his discovery, enabling the rapid advances in X-rays that followed his seminal discovery.