The Scientist That Believed Intelligent Alien Life Existed On Mars

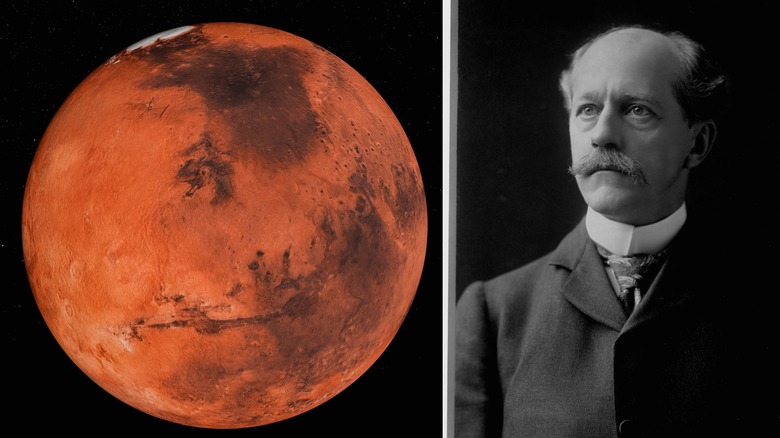

The planet Mars is the most thoroughly surveyed celestial body aside from Earth itself. Generations of space probes and rovers like Curiosity have collected images and material samples of the red planet, and they've gifted us a wealth of valuable data. To the disappointment of many, none of that evidence suggests that there is active alien life on Mars, and certainly no intelligent lifeforms on par with humanity. However, at the turn of the last century, decades before the days of rovers and satellites, one scientist was convinced that Mars not only hosted life, but in fact was home to a complex and highly advanced alien civilization. It's the kind of theory that would get someone dismissed as a crackpot today, but it wasn't some amateur peddling this theory; it was America's most famous astronomer.

The name of Percival Lowell dominated discussions about astronomy in the United States from the 1890s through the 1910s. Although many of his theories met backlash from fellow scientists, he was nevertheless an incredibly sought-after lecturer, achieving a level of celebrity uncommon for academics even today. Lowell believed that canals on Mars, which telescope technology had only just revealed at the time, were evidence of an advanced society. Martians, he claimed, had extensively terraformed their own planet, creating a vast irrigation system for agricultural purposes. He died firm in his beliefs, and although his theory was roundly debunked by later probes, the images Lowell conjured of a Martian civilization remain deeply ingrained in pop culture to this day.

Percival Lowell's remarkable career

Percival Lowell was born in 1855 to a Bostonian family of rarified status. So prominent was his lineage, that there are towns in Massachusetts named after both his paternal and maternal ancestors (the towns of Lowell and Lawrence, Massachusetts, respectively). The great fortune amassed by his father's textile empire afforded Percival a top-rate education, and he graduated from Harvard in 1876 with a distinction in mathematics. He initially followed his father into the textile industry, before making the kind of move that only a child of great wealth can and spontaneously moving to East Asia. He spent his 30s in Japan and Korea, serving for a time as a foreign secretary and authoring several books.

Despite success abroad, Lowell felt drawn to a completely different field of work: astronomy. He had acquired a telescope in his tween years and was particularly fascinated by Mars and the potential secrets beneath its visible polar ice caps. In the 1890s, Lowell encountered the work of Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli, who at the time had just discovered the existence of natural channels on the Martian surface. Schiaparelli referred to the grooves as "canali" in his native Italian, which was mistakenly translated to "canals" in English. Lowell took the faulty translation to imply that the grooves on Mars were artificially made. He theorized that an advanced Martian civilization had dug the canals to route water from the poles towards vast agricultural developments. He lacked evidence beyond the appearance of lines on Mars' surface, but that didn't stop him.

Time has not been kind to Lowell's theory

Percival Lowell's Martian canal theory was never widely accepted by his fellow scientists, who balked at his lack of evidence. However, his ideas became very popular amongst the greater public thanks to three books he published on the subject. Lowell's name carried so much weight at the height of his fame, that in 1906, The New York Times even ran the front page headline "THERE IS LIFE ON THE PLANET MARS; Prof. Percival Lowell, recognized as the greatest authority on the subject, declares there can be no doubt that living beings inhabit our neighbor world." Lowell's work was still immensely popular by the time he died in 1916, and his doubters weren't able to definitively debunk him until 1965, when the Mariner 4 spacecraft performed the first successful flyby of Mars.

Even though Lowell's Martian canal theory turned out to be wrong, he still left a significant imprint on modern astronomy. Perhaps his greatest contribution to science was funding the construction of the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona. Built in 1894, it was the first major research observatory located outside of a university town, which protected it from light pollution. Lowell used the observatory to study Mars, as well as another passion of his: hunting for the ninth planet. In 1930, Clyde Tombaugh did actually discover the dwarf planet Pluto from Lowell Observatory. Today, the observatory is enshrined as a U.S. National Historic Landmark, and it continues to keep Percival Lowell's name alive through contributions to science.