The Largest Flying Bird Today Is Nothing Compared To This Prehistoric Terror

Birds are majestic creatures. The bald eagle, for instance, has been on the Great Seal of the United States for nearly 250 years. Plus, various species of birds have earned the honor of becoming state birds, like the American robin in Wisconsin. None of these, though, are among the largest flying birds in the world today. And even they pale in comparison to the biggest flying bird to ever live on the planet.

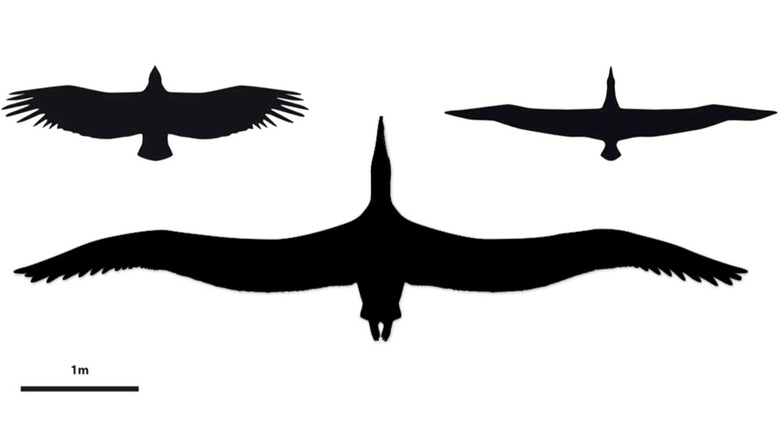

By mass, the largest bird that can fly is the kori bustard — one of the animals in the savanna grasslands of southern Africa — which can weigh up to 42 pounds, and has a wingspan that reaches 9 feet. But when it comes to wingspan, the wandering albatross has it beat with a wingspan an average of 8.2 to 11.5 feet.

While these are amazing measurements, they don't hold a candle to those of the Pelagornis sandersi. The remains of this prehistoric species were found during an expansion of the Charleston International Airport in 1983, when it had to be unearthed with a backhoe because it was so large. Thirty years later, ancient bird fossil expert Dan Ksepka was visiting the Charleston Museum when the remains were rediscovered in a storage drawer.

A 2014 paper published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences puts the specimen's wingspan at 21 feet. However, physiological scaling data using various combinations estimate that these prehistoric birds could have had a wingspan of 19.5 to 24 feet and weighed 48.5 to 88 pounds — all of which dwarf currently living birds on Earth.

What scientists know about pelagornithids so far

The P. sandersi isn't the only bird of its kind to have existed on Earth. It belongs to the Pelagornithidae family of extinct pseudotoothed (bony-toothed) birds that was last known to exist 2.5 million years ago — right before the Quaternary ice age started. Based on the dating of various fossils, it's believed that the pelagornithids survived the mass extinction of the dinosaurs 65 million years ago.

Other than when they lived, scientists have estimated that this family of birds could fly and glide in the air for weeks at a time, covering great distances over the Earth's oceans. P. sandersi specifically is believed to have traveled at up to 40 mph and would utilize dynamic soaring — swooping down toward the surface of the water and pulling up to catch a faster air current to remain in the air. Because of the wide wingspan being difficult to flap quickly, though, researchers think that it may have waited for a wind gust or would run downhill in order to get into the air. And it could stay in the air because its bones were hollow, like most other species of flying birds today.

Rather than actually having teeth, the pelagornithids had sharp bones or struts protruding from their jaws. These protruding bones allowed the birds to snap up fish and squid from the sea while gliding overhead. More specifically, P. sandersi likely ate these and other soft-bodied creatures in the waters that now line North and South Carolina. Pelagornithidae were also denizens of Antarctica, with fossils having been found on Seymour Island off the coast of the Antarctic peninsula. At the time (between 55 and 35 million years ago), the continent had a warm climate and wasn't the glacial landscape that it is now.