The Bizarre Parasitic Plant That Smells Like Rotting Flesh

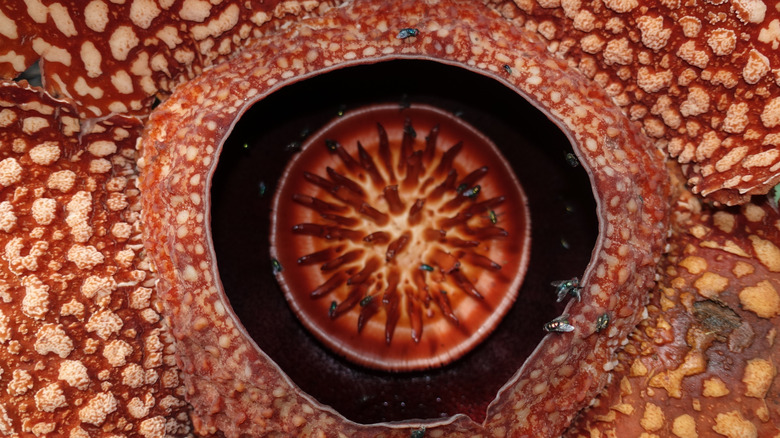

If you thought all plants survive by photosynthesis, you'd be dead wrong, and you need look no further than the world's largest flower species. Found in the rainforests of Southeast Asia, Rafflesia arnoldii is a blood red blossom that can top three feet in diameter and weigh more than 20 pounds. It is the most famous member of the Rafflesia genus, which includes 42 known species, primarily found on the islands of Indonesia and the Philippines. Aside from their remarkable size, these plants are best known for a particularly off-putting trait: they smell like dead bodies.

Rafflesia are sometimes called "corpse flowers" due to their stench, although that name is also used for another flower, Titan arum, which also grows in Indonesian rainforests. They stink for good reason, because as repulsive as rotting meat is to us, there are certain creatures that absolutely adore it. The main pollinator for Rafflesia are carrion flies, whose favorite food is decaying flesh. The flowers' stench attracts these pollinators, while their bumpy crimson appearance backs up the act by looking like a great pile of guts.

Size and stench have made Rafflesia famous, but these aren't even close to the plants' most fascinating trait. Unlike most flowers, Rafflesia has no leaves, no stems, not even any roots. It survives as one of the rainforest's most extreme parasites. The flowers cling to a host plant, stealing its food and water. It's a sinister means of survival, and scientists are only just beginning to understand how it works.

The weird and wonderful Rafflesia life cycle

In contrast to the Rafflesia flower's massive dimensions, its seed is only as big as a fleck of sawdust. From this seed, a series of tendrils emerge, similar to the way a fungus grows. These tendrils are microscopically thin, sometimes just a single cell in width, but they can grow to more than 30 feet long, ensnaring the Rafflesia's host plant.

Rafflesia don't just grow on any old plant they find. The seed must come in contact with a vine of the Tetrastigma genus, a group of wild plants within the grape family. There are over 100 different Tetrastigma species, and Rafflesia have been found to grow on multiple members of the genus. The parasite's tendrils are so fine that you cannot even notice them weaving their way through the bark of their host. It is only once the flowers begin to bloom that the invader finally reveals itself.

Rafflesia can lay dormant within its host for months, even years, but inevitably, a little bud will poke its way out. At first, it looks like nothing more than a small cabbage, pale and unremarkable, but after about six months to a year and a half, it will bloom into the noxious monstrosity the plant is so well known for. The entire Rafflesia life cycle can take as long as four years, but the blooms only last about a week. After that, they decompose, and with no roots or shoots to spawn another flower, the whole plant dies.

Rafflesia plants are facing the threat of extinction

Rafflesia are so remarkable that they challenge our notion of what a flower even is. Their parasitic lifestyle, and the fact that they don't even have the gene necessary to achieve the functions of photosynthesis, have led some to argue that Rafflesia shouldn't even be classified as angiosperms, that is, flowering seed plants. Unfortunately, studying this fascinating flower is going to get more difficult because they are facing serious threats from the impact of humans.

All 42 known species of Rafflesia are currently classified as threatened, and a 2023 study published in the journal Plants, People, Planet reported that 60% of those species are critically endangered. The devastation wrought upon these plants has come from a combination of deforestation destroying their natural habitat, and poaching, done to take advantage of Rafflesia's purported medicinal benefits and aphrodisiac properties.

Sadly, Rafflesia is not well adapted to overcome this challenge. The species is already scarce because it has specifically adapted to have low numbers in order to not overwhelm Tetrastigma plants and accidentally kill their hosts. Further complicating things, Rafflesia are only able to reproduce when two flowers of each gender are close to one another. With habitat loss thinning out the herd, so to speak, these couplings are becoming less and less common. Conservationists struggle to breed Rafflesia in captivity due to its need for very precise conditions, so preserving its natural habitat is the only viable way to save corpse flowers from the grave.