Scientists Finally Confirmed The Existence Of Runaway Black Holes

Astrophysics is a field in which theory usually comes first and observation comes afterwards — sometimes decades later. For instance, Einstein's Special Theory of Relativity predicted gravitational lensing, but it wasn't until years after his death that telescope technology had improved enough to confirm its existence. Now, thanks to the extreme sensitivity of the James Webb Space Telescope, another five-decade-old theorized phenomenon has finally been observed: runaway black holes.

"Runaway black holes" are black holes that travel through space at extremely fast speeds, untethered to closed orbits by the gravity of galaxies. They're kind of like interstellar comets, such as the recently-observed 3I/ATLAS comet, which scientists have watched tearing through our solar system from mysterious origins beyond. Yet, while runaway black holes and interstellar comets are quite different in size, both are sent careening on their trajectories by similar processes. When one massive object and another pass each other at the right distance, speed, and angle, their gravities may fling them off into space at blistering velocities. In the case of the newest observation, the scientists predict that the supermassive black hole was slingshot into high speeds by at least one other supermassive black hole.

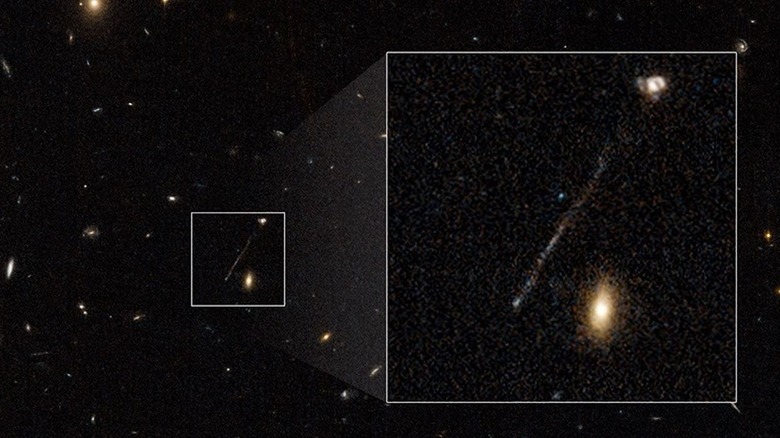

While we can't directly see a runaway black hole, we can see how its path interacts with stars as its gravity pulls them into its wake. According to a yet-unpublished 2025 joint paper posted to Arxiv, scientists have found a trail of stars that appears to have formed from a high-speed massive object. It forms a 200,000-lightyear contrail of stars trailing behind a bulbous head of stars called a "supersonic bow shock." Crunching the numbers, the team predicts the supermassive black hole that carved the path was "running away" from its host galaxy's gravitational center at a speed of 2 million miles per hour.

From a blurry shot in the dark to high-res imaging

The contrail comes from a region of space roughly 7 billion light years away, which explains why it required the James Webb to capture a high-quality image of it. Theoretical models, however, have predicted runaway black holes were possible since the 1970s. But theoretical models on a piece of paper and photographic evidence are two different things.

In 2023, a team led by Yale's Pieter van Dokkum first found a blurry image of the contrail of stars in archival photos from the Hubble SpaceTelescope. That original image looked more like a faint streak of light rather than an individual collection of stars. But once the team was afforded the opportunity to direct the more powerful James Webb Space Telescope, the contrail became clear. Most importantly, the bow shock, predicted by the theoretical models, became visible.

A cosmic bow shock takes the same shape as a boat's path through water. As the bow of a ship moves through water, it compresses the water in front of it, which then flows around the bow and rejoins in a thinner line behind it. On a cosmic scale, gravity, not the collision of water particles, forms the same pattern. As a runaway black hole flies past stars at millions of miles per hour, its intense gravity clusters the stars near its head, or "bow." But at such velocities, most of the stars are then dispersed in the wake, rather than getting sucked into the black hole's event horizon. The result is a trail of stars that leave behind visible evidence of an invisible object. The paper hasn't been officially published yet, but van Dokkum and his colleagues are already on the hunt for more "smoking-gun" evidence of runaway black holes.